Problems for Adyen and Paypal in the competitive payments landscape

Thoughts on the industry

A bird-eye’s view of the payments industry

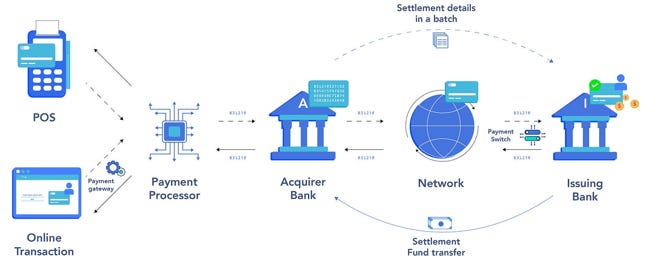

The payment ecosystem has become a rather complicated value chain with the move to digital payments. In prehistoric times, when payments were made in cash, the federal reserve would issue notes which could easily be used in transactions with immediate settlement. In the world of digital payments however, the key problem was knowing whether the buyer actually had the cash available in his bank account. So a payment network was installed which would check if the money was indeed there. Subsequently, the money would be transferred over from the purchaser’s bank account to that of the merchant. As both of these had to be connected to the same network to make this happen, this automatically become a highly consolidated industry with typically only a few number of players per country. The most widely recognized names operating in this space (payment networks) are Visa and Mastercard and are typically seen as the highest quality investments in the payments industry due to their wide moat.

At the point of sale, the merchant acquirer who manages the merchant’s bank account, provides a gateway so that a secure connection from the method of payment to the network can be made. Initially this was a terminal, but later on this would become fully digitized as well with a gateway running in the browser. Classic examples here are the Paypal button and the little form where you can type in your debit/ credit card details.

The overall ecosystem illustrated:

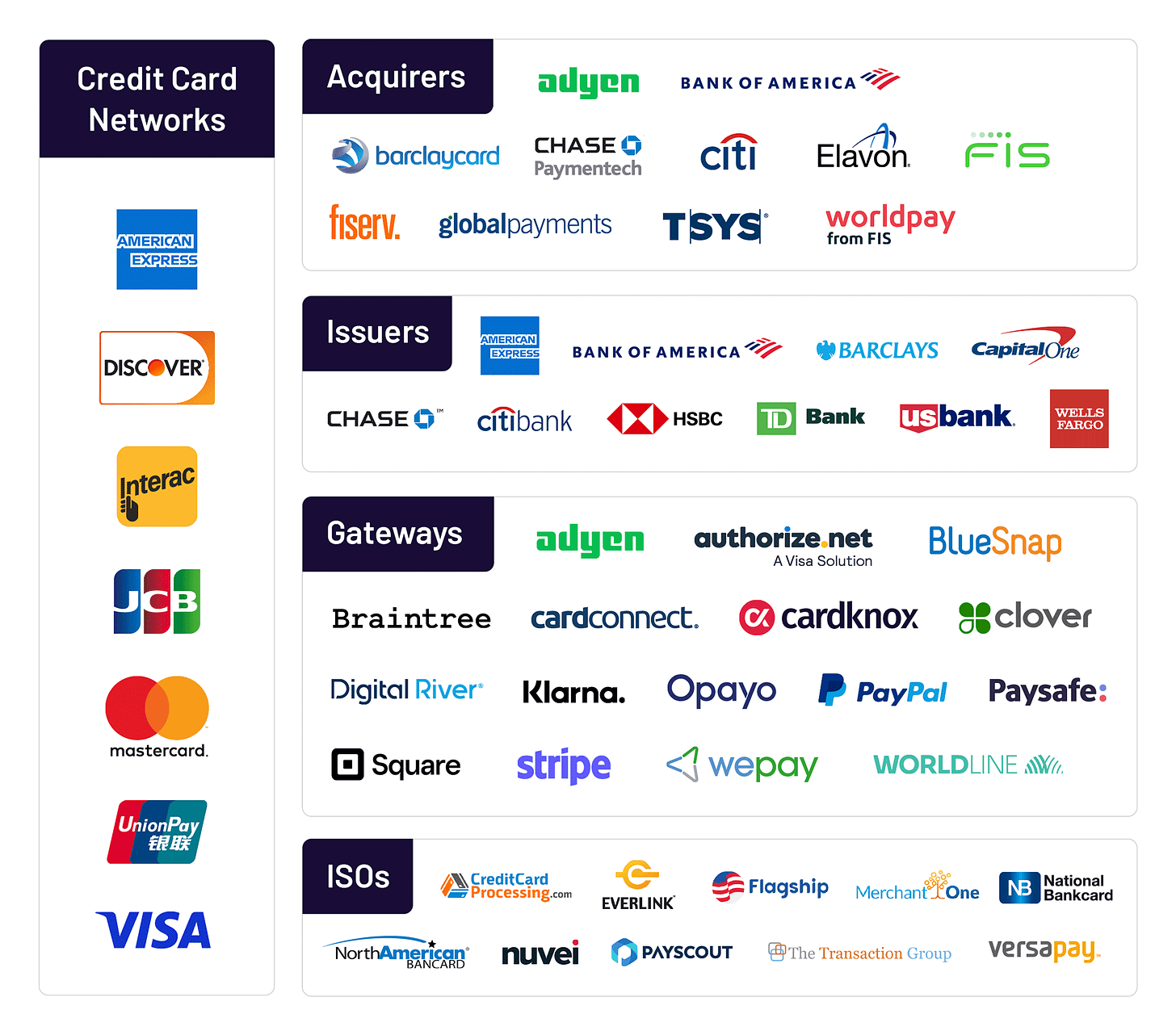

Also merchant acquiring was actually a pretty decent business. Typically you would have a handful of players in a country, and they would make high margins on smaller merchants with a take rate of around 3%, although in emerging markets with higher levels of fraud this can go up to 5%. Large merchants such as a Walmart on the other hand, providing large volumes, would get large discounts.

Some of the more recognizable names in merchant acquiring include Worldpay, Chase, Shift4, and Wirecard,.. but the latter is a story for another day (which goes somewhat like Enron).

An overview of some of the more notable players in each of these niches are presented below:

An introduction to Adyen

The ecosystem above shows that Adyen is active both in acquiring and in gateways. What made them really unique originally is that they have a global platform, running in a single codebase, able to accept the unique payment methods and currencies of around the world, and able to connect with local payment networks. The typical old-school merchant acquiring competitors on the other hand have legacy systems, cobbled together by acquisitions, giving them substantial problems in both cross-border integration and scaling. Worldpay is a notorious example here.

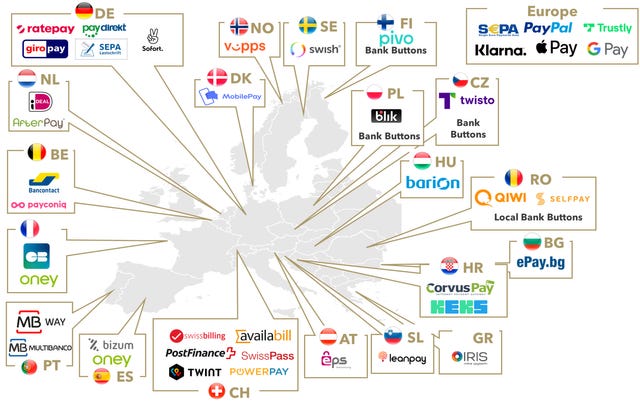

The image beneath highlights all the popular digital payment methods per European market. Adyen, having been born in Amsterdam, has a platform which is exactly designed to deal with this complexity.

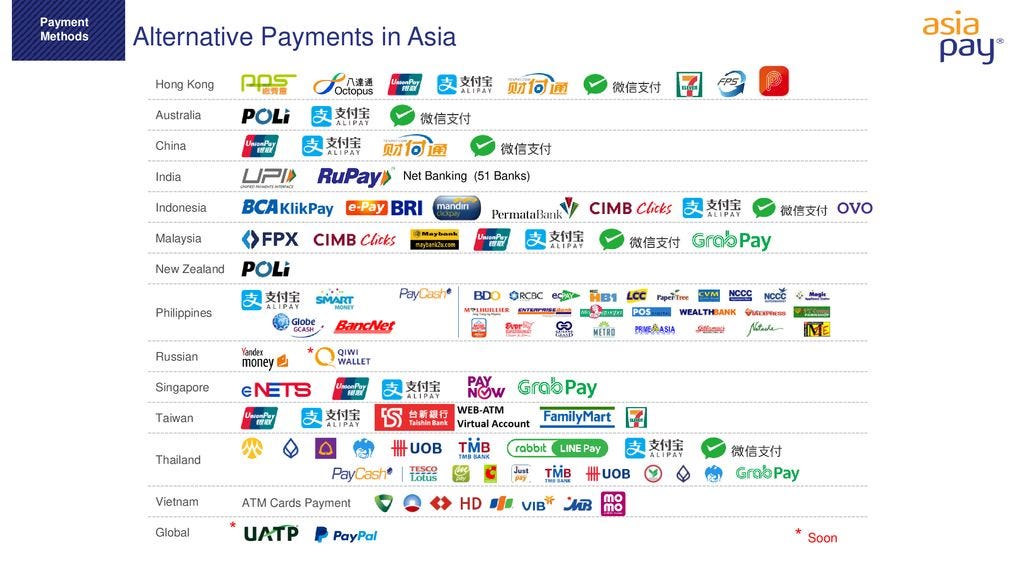

Similarly the Asian fintech scene has seen an explosion of local innovation:

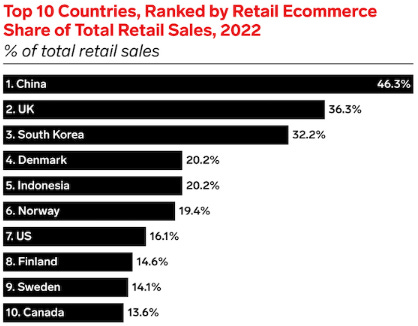

As a result, Adyen’s platform is really ideal for a large multinational enterprise who wants to be in an easy position to collect payments around the world. Its customers include some of the world’s most recognizable brands such as McDonalds, Facebook, Microsoft, Uber, Spotify, Netflix, H&M, Ebay, and Airbnb. The other attraction of Adyen is that you grow with these brands. And you get exposure to the rising penetration of e-commerce in these countries:

This business model has been extremely successful. When looking at the global enterprise e-commerce market, Adyen already has a 20% market share. However, enterprise e-commerce is only 10% of the overall merchant acquiring market, meaning that Adyen only has a 2% market share in the wider merchant acquiring market. This highlights the fragmented and competitive nature of this industry with over 3,000 merchant acquirers competing globally, although mostly only on a local level. The positive here is that there is lots of prospect for consolidation with legacy acquirers being replaced with modernized platforms.

That said, if you only have to provide in-store processing for merchants, typically you just need a regional datacenter which can provide low latencies in accepting payments. It really isn’t that complicated. So I suspect that Adyen will remain oriented towards the larger multinationals for its core business, although they have also started providing software for smaller merchants operating over peer to peer platforms (e.g. Airbnb) to manage their businesses. More on this below.

A customer can connect to Adyen’s platform with API calls from their codebase, i.e. within their web app or within their smartphone app. This a simple encrypted JSON-style call which gets transmitted over the internet to Adyen’s datacenters. Within the encrypted JSON message, a secret token will be passed along to verify the customer making the call. Adyen will subsequently take care of the transaction and send a message back that the payment has been accepted, or alternatively that a particular type of error has been found and that the payment can’t be accepted.

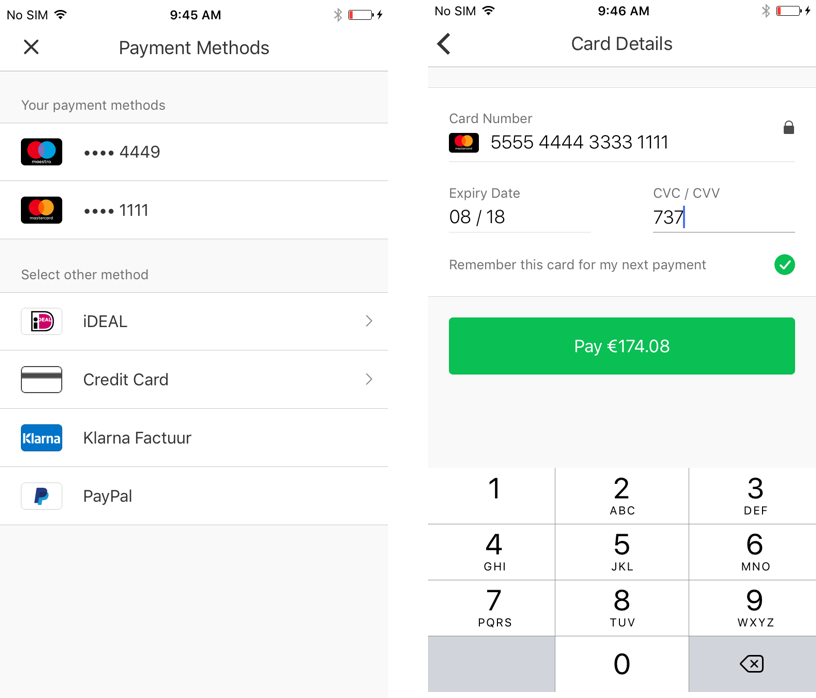

A customer can integrate an interface for accepting payments within their (web) app exactly the way he wants. Although Adyen also provides templates which can be inserted into the app and subsequently customized with coding such as CSS. So McDonalds might go for a red looking background with yellow letters in the McDonalds font for example. This level of customization is a big positive for large brands.

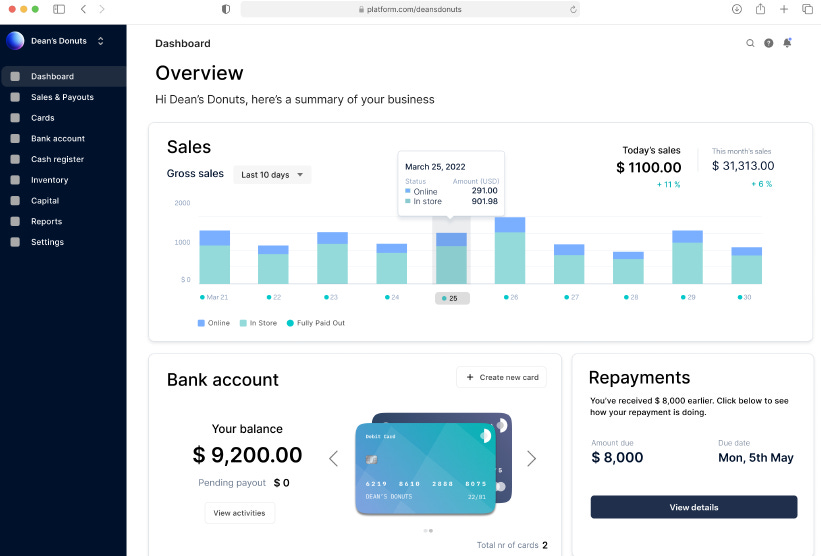

The company has also started to provide dashboards, similar to Square or Toast, so that a small merchant on a peer to peer platform can easily keep track of his business. This isn’t really in demand from Adyen’s enterprise customers, as they would access this data from their ERP (e.g. SAP) and analytics (e.g. Snowflake) systems.

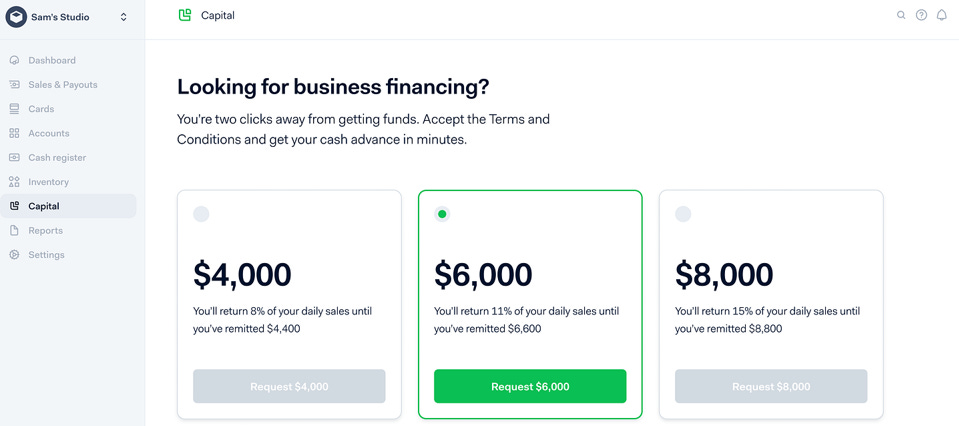

Dashboards also provide Adyen with the opportunity to sell additional services, of which the most interesting is BaaS (Banking as a Service). As the platform provider knows the cash-flow profile of each merchant, smaller type loans can easily be made if there is the need for an investment to grow the business. These loans are provided by a financial institution such as a bank, private equity, or an asset manager, and the customer automatically pays these back from the revenues he generates over the subsequent year.

As Adyen also has a banking license in a lot of countries, the peer to peer platform can issue a business banking account to these smaller merchants, including a debit/ credit card. The advantage for the small merchant is a faster receipt of payments, as well as having everything in one platform, from banking to their business dashboards. The attraction for the platform partner is that Adyen is invisible to the customer, so Airbnb for example could leverage Adyen’s tech and banking capabilities, but branding everything under their own logo.

Adyen’s CEO discussed the opportunity in platforms at the Goldman conference: “We did some research where we see that about one-third of SMBs get payments from platforms today, but that will likely go to something like three-fourths of SMBs. So making sure that we have an offering that helps these platform customers is really key for us. And there, we're seeing really strong traction. Excluding Ebay, we grew 82% in the first half on the platform side. That's especially in Europe and the US.”

Adyen’s website gives some further stats: “Our research found that, by offering embedded financial services, platforms could unlock a potential revenue uplift of up to 70%. The market for SMB embedded finance is still at an early stage of development, with less than 5% of penetration.”

Another area where Adyen is investing strongly is omnichannel, which is useful for retailers that both sell from physical stores as well as online. This enables them to track customers across these channels, so that better promotions, services, and more relevant advertising can be offered. If a consumer buys an item online for example, the platform could tell the retailer that this customer lives close to a certain store, allowing for same day delivery.

Adyen’s CEO detailed how a large chain like McDonalds is using them for omnichannel: “If you had basically discussed this like 3, 4 years ago that a fast food chain would work with a processor like ourselves to accept payments, I would have said that likelihood is relatively low because they just need pipes at a counter to process quickly. But now it's completely shifted because it is about consumer insight. It is about how making sure that no matter if you pay in the app or at a counter that you have to write the information. So it opens up a lot of new verticals, and that's what we're focusing on right now. The unified commerce opportunity is huge. We're ahead of competition, like there's no global player that can offer this in a single platform.”

Adyen’s founding & engineering ethos

Adyen stands for ‘start again’ in the language of Suriname, a reference to the fact that this was the founders’ second payments company. The first, Bibit, was sold to Worldpay in 2004 (as I told you, a company cobbled together by acquisitions). After this first experience in the industry, the founders had learned about all the problems with legacy systems (having worked two years at Worldpay post acquisition). And they decided that a new, integrated platform would replace these legacy providers. They got to work in their Amsterdam apartment.

Pieter van der Does, Adyen’s co-founder in an interview with Techleap detailed the company’s background, history, and culture: “When we sold Bibit to Worldpay, we had so many lessons learned. And when we sold the company, we didn't think we would go back into payments. But 2 years later, we regrouped and thought of starting a company again. We started a company called Adyen. At that time there were so many fragmented solutions. Our idea was to build in-house something that connects directly to the endpoint of payment and does not make a patchwork of systems. We believed that if you could make this product of the highest quality possible, then you’d be able to sell it to the best companies in the market. So we had a very unusual market entry strategy and a very ambitious plan - we know this market, we're going to build something that outperforms and we directly target the high-end.

Our first sizable merchant was in 2011, and we started in 2006. That took us 5 years. One of the difficult things to overcome at the beginning of your journey is that you need volume in payment. Breaking through that problem is what took us time. And then a few years after 2011, we started to build a point of sale because we thought it's great to provide payments for internet companies. We also saw that a lot of internet companies, such as CoolBlue, moved to physical stores, which was unexpected at that time. While we felt that the infrastructure we built actually worked really well for physical stores, it was particularly excellent for companies that had both online and offline presence.

We have turned down many offers along the way from the very first days when we were founded. Already then we got an offer to stop doing what we do and be acquired as a team. So along the way, on the road to IPO, we got many offers, frankly. And it’s not always easy to turn them down with your shareholders. After selling Bibit, I stayed in the company for another two years, and as a result I had to run it under the umbrella of a larger company that made all sorts of decisions that I wouldn't personally make.

This is how we approached our first investment round with the first big VC: we don’t want to give board seats because we are building a large company. And if you build a large company, you know that at a certain point you will need an independent board. So we didn’t want to give anything other than common shares.

With Adyen we have a great preference for simplicity. Because if it’s simple, it’s easier for us to control it. So therefore we never made an acquisition. We only run one system. We only have engineers that are educated in the languages we use within the company. The board still oversees every hire, regardless of the role. You cannot be hired at Adyen without speaking to one of the six board members. The reason we do it is to put the bar high to ensure that only the best talent joins Adyen.”

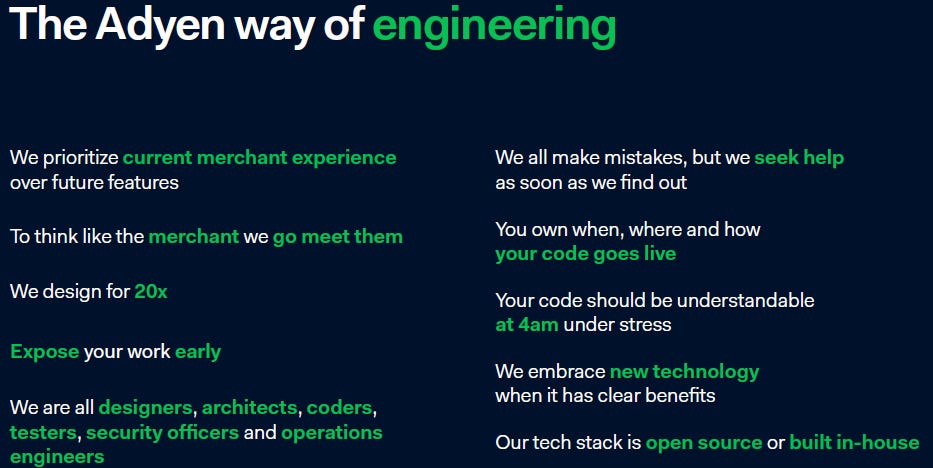

The ethos which Adyen’s founders have been installing in the company:

Thoughts on Adyen’s H1, Paypal, and the competitive payments landscape

So after this long introduction, even if you’re new to the payments industry, you should have enough background now to understand the variety of problems which I’m about to go into. Theoretically, Adyen’s story should be of interest to investors, i.e. a platform which currently has a competitive advantage and with a long runway for growth, both as they replace legacy systems and and as they grow together with the rise of e-commerce. As the company’s cost base grows more slowly, we should get great operating leverage in terms of earnings growth. And obviously, this is an extremely well-managed business, designed with simplicity and low-cost in mind, with the whole platform running from one codebase. Which has translated into strong margins.

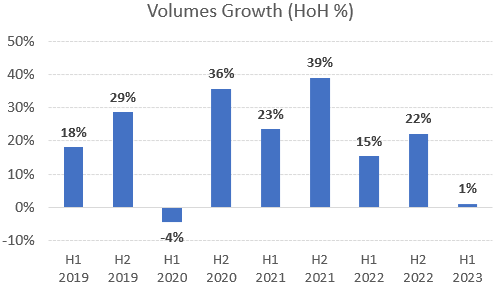

However, at Adyen’s recent half year results, sequential volume growth (transactions processed) came in at a measly 1%:

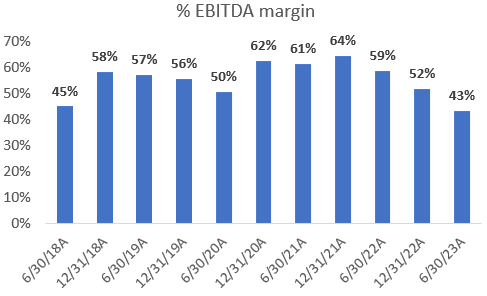

On top of that the company’s margins took a nosedive coming in at 43%, a historic low:

The billion dollar question is what’s going on here, are we looking at a temporary blip or has the company started struggling with more structural and competitive pressures?

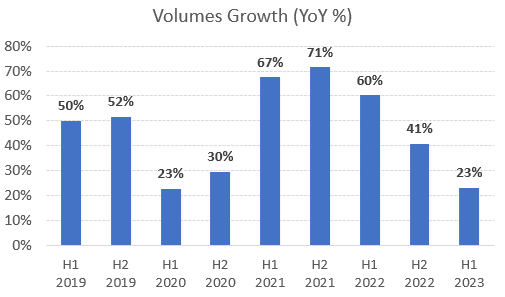

Well, the results aren’t as bad as implied in the two charts above. The first half of the year is the seasonally weaker half, as it doesn’t include the Christmas holidays shopping period and the summer vacation spending. Looking at revenue growth on a year over year basis, the easiest method of stripping out seasonality, we still saw 23% revenue growth. Although this was far below what the market was expecting and still a historic low.

On the margin side, the company is guiding that this will be a year of headcount increases, to drive the R&D in peer to peer platforms and omnichannel, after which headcount growth can be slowed down again. So we’re currently in an investment phase which should drive accelerated revenue growth and operating leverage in the coming years.

The pressure point for the weak result seems to come from the competitive environment in the US e-commerce market, which Adyen has been targeting for growth. Adyen originally grew in the European e-commerce market, where due to a plethora of localized payment methods and currencies, the company had an obvious competitive advantage. In the US on the other hand, payment methods are much more limited. If you’re able to accept Visa, Mastercard, American Express, Paypal, Google Pay, and Apple Pay, you’re probably in a position to accept payments from almost any consumer. And authorization rates will be extremely high already. Adyen due to their strong localized know-how will be able to increase authorization rates in emerging markets for example, but this advantage isn’t a factor in the US. This results in the US being a much more competitive market, with more processors being able to compete as well as the legacy players.

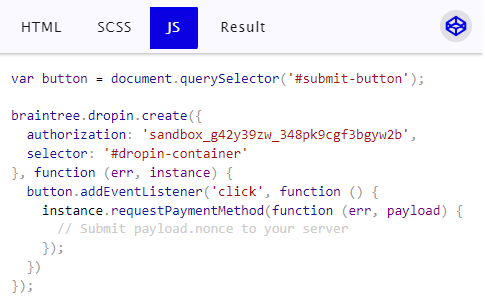

The competitor which is frequently being cited as competing aggressively with Adyen on price is Paypal’s Braintree. Braintree is a gateway and acquirer similar to Adyen which can easily be integrated into a website and app. Similar to Adyen, this is a gateway targeted at mid to large corporations who like to customize their payment experience. The below image highlights how you can insert some Braintree-provided Javascript into your code, which will provide you with a nice widget which you can customize to fit your digital store.

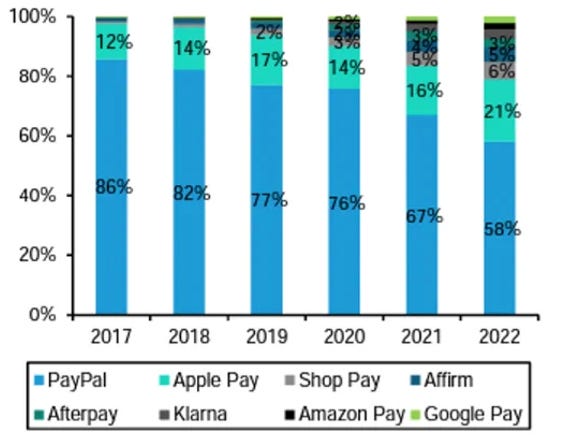

A contributor to Paypal’s aggressive stance in the Braintree business is that their famous checkout button has come under pressure. Bernstein calculates the following share losses in the US, with especially Apple Pay gaining share but also Shopify with Shop Pay and buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) providers such as Affirm.

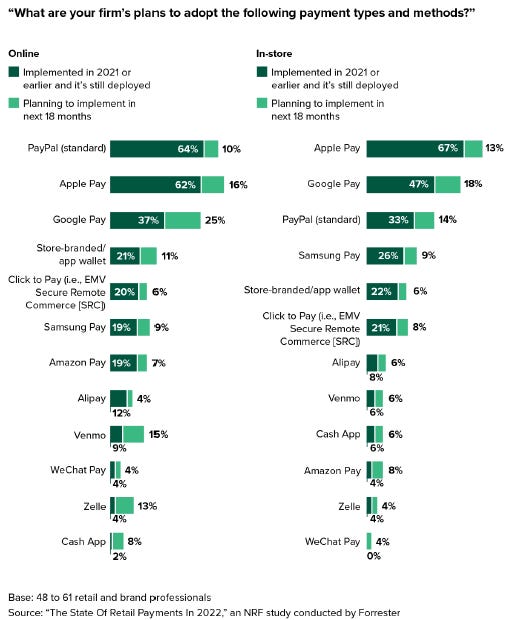

And the pain isn’t over. According to a study by Forrester for NRF’s state of retail payments in the US in 2022, Paypal is still leading when it comes to online payments, however, more are planning to offer Apple Pay within 18 months. This would give the latter the lead. Clearly also Google Pay has strong momentum, including those retailers that are saying they will adopt it, this would make the gateway’s acceptance rate jump from 37% to 62%. Both of Apple Pay and Google Pay lead in in-store payments with Paypal only coming in third.

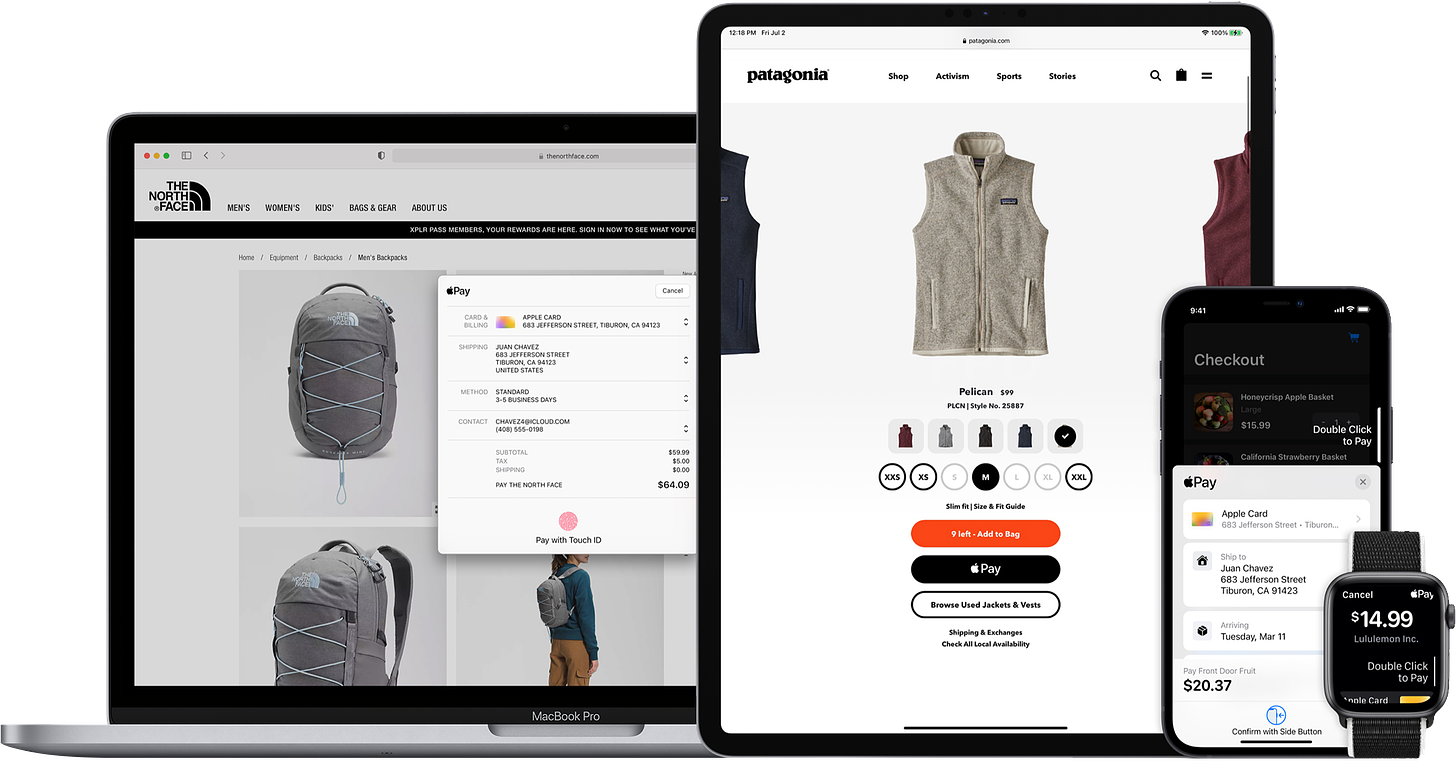

You might think that Apple is only 50% of handsets in the US, so that they will only be able to capture 50% of the payments market. Well, iPhone users are twice as affluent on average, making them two-thirds to three-quarters of consumer spending. That’s a big chunk of the market which Apple Pay could grab. Naturally Apple is making their payment button pop-up everywhere they can:

Forrester’s results are sort of in line with what I’m seeing anecdotally living in London. Over the last year, I’ve started seeing the Google Pay button more frequently than Paypal’s when shopping online. And it’s also usually ranked above the one from Paypal, as Google’s take rates are lower. A typical checkout layout I’m coming across these days is highlighted below. In my opinion, the Paypal button has become fairly commoditized..

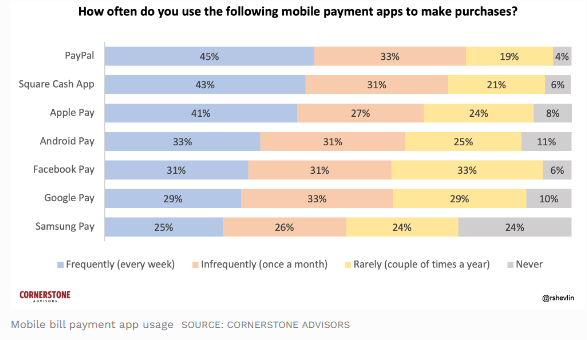

Also when it comes to mobile payment apps, Paypal is facing a competitive environment with respondents in a study from Cornerstone using a wide variety of apps. The positive here is that there is still plenty of room for growth with mostly young people only using these. But the negative is that Paypal is not making any money here, with very low monetization rates.

Going through all this data my suspicion is that Paypal’s take rates will likely be heading (further) south in the coming years, mainly coming from further market share losses in their bread-and-butter Paypal button business. And I guess Paypal’s management is making the same calculation — “If only there’s a way to protect our Paypal button business..”

This brings us back to Adyen and the competitive environment it’s facing. If Braintree successfully takes share as a payment processor, they can promote the Paypal button to have a prominent position on the checkout page, and this is where they can make high margins. Following this reasoning, it even makes sense to sell Braintree at zero or negative profits, basically using the business as a loss leader.

Paypal’s CEO at the Goldman conference: “We’re doubling down on our unbranded platforms, we're having tremendous success on that, which kind of doubles down on our checkout again because when we implement our unbranded platforms into merchants, they automatically upgrade to our latest checkout integrations. And when you're on our most upgraded checkout solution, we either gain or hold share worst case. And so we stopped losing any share that we might have and we hold or grow.”

Morgan Stanley estimates that Braintree is currently pricing 50% below Adyen in the US, while increasingly being able to match Adyen’s capabilities in this market. At the same time, Braintree is also building out their international functionality. Their website mentions they can handle 130+ currencies in over 45 countries.

However, the hole in this tactic is that there are quite a number of payment processors like Adyen and Braintree, I’ll discuss some of them later on, and Paypal will have difficulty maintaining their gateway share with the checkout button at these other providers. As well as with the legacy acquirers. Further share losses seem extremely likely in my opinion.

The company also announced a high profile win for Braintree: “In March, we deepened our relationship, establishing PayPal as one of Booking.com’s strategic card processors globally. We migrated international processing to the Braintree platform in only one month, minimizing the disruption that is usually involved with changing providers. Since transitioning to the Braintree platform, Booking.com has seen strong performance in authorization rates in the regions where we partner together.”

Booking.com is a signature client of Adyen, as they need to accept payments within Europe in all sorts of currencies making use of the local payment methods. So Braintree has taken a part of this business, as Booking is also still using Adyen. But it could be that Braintree is only handling the US side of the business. Later on, I’ll dive into the methodology how enterprises are shifting volumes between various payment providers. More on this below.

Going back to the Goldman conference, Paypal’s CEO had some more interesting data to share with us: “When a merchant uses PayPal, 15% to 20% of their checkout typically comes through us. But that means 80% to 85% of their checkout is card entry or other methods.”

My take — a market share of 15 to 20% at penetrated merchants is not a strong position, especially as the trend has been on a downward slope.

Paypal is also going after Stripe with the development of the PCPP platform, aimed at servicing small merchants. Paypal’s CEO: “It's an extremely large TAM. Most importantly, it is a market we have not really touched with products in a long time. We've spent years developing PPCP. We just rolled it out. It will be fully rolled out through Europe as well as the US and certain select markets in APAC. And it's focus, it's our unbranded PSP (payment service provider) platform for small businesses and channel partners. It's going right at Stripe. We've had a tremendous initial success there. We've got Shopify, WooCommerce, Adobe, 25 other channel partners signed up to roll out PPCP. We've got 2.5 million merchants with one click which can move over.”

Later on he detailed some more of the logic of taking this route: “And so when you're upmarket, especially in the US, it's pretty much commoditized on the payment side, very low margin business (i.e. Braintree). Now there are ways of increasing margin on that (he’s referring to promoting the Paypal button). But downmarket, even in the US and especially overseas, it's a high-margin business.”

This sounds very similar to what Adyen has been implementing in what they call their platforms business, i.e. the servicing of small merchants on peer to peer platforms.

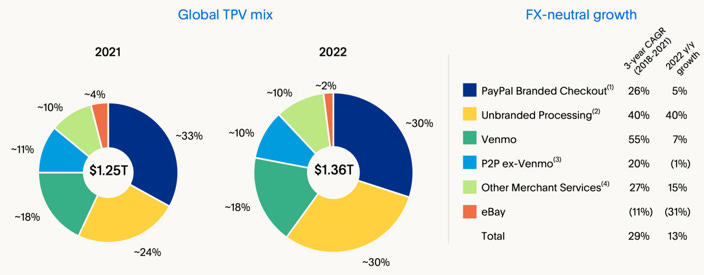

Below is an overview of Paypal’s business mix, 30% of processed transaction volumes are coming from Braintree (‘unbranded’) and this category is growing strongly in the mix, at least in terms of volumes processed. You can also see that both Paypal and Venmo are losing market share — whereas the e-commerce market is growing at a 10% rate, both the Paypal button and Venmo are only growing transaction volumes at 5% and 7% respectively. But the worst performance came from P2P ex-Venmo, which is the sending of peer to peer payments over the Paypal app, which was down 1%. Other merchant services are growing well as well. Overall, the only asset that’s gaining share is Braintree, at little profits with Credit Suisse estimating Braintree to only contribute 5 to 10% to Paypal’s gross profits.

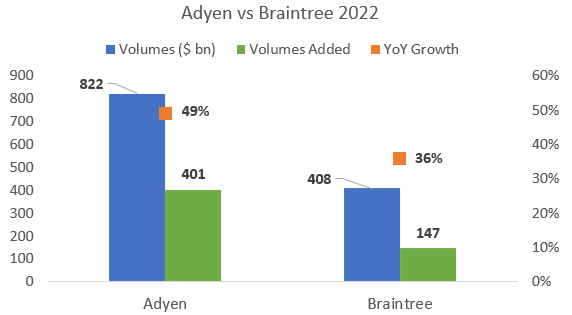

I calculate Braintree being around half the size of Adyen in terms of volumes in 2022 and their growth rate coming in at 36% vs Adyen’s 49%. Resulting in Adyen adding $400 billion of processed volumes compared to Braintree’s $147 billion:

However, this year Braintree has started outpacing Adyen when looking at growth rates, with Adyen only growing in the low twenties and Braintree still growing at around 30%. Adyen is still adding more volumes in dollar terms, although the difference has become less strong, resulting in mathematical share gains for Braintree.

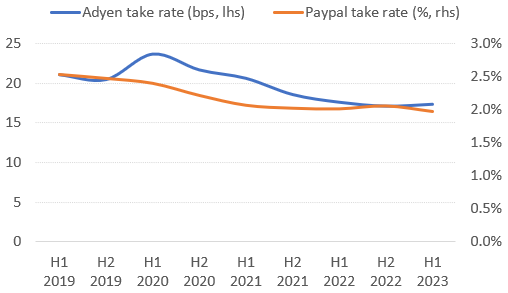

Both companies’ take rates have been on a sliding trend, but business mix is playing a role as well here. As Adyen is growing in the US, take rates automatically come down as the US market is lower margin compared to Adyen’s core European business where competitive dynamics play a smaller role. Similarly, as Paypal’s Braintree business grows in its business mix, take rates are coming down. Another factor is modularization, where some corporations use Adyen and Braintree purely for processing, outsourcing other value added services such as fraud and sanction detection to specialized providers.

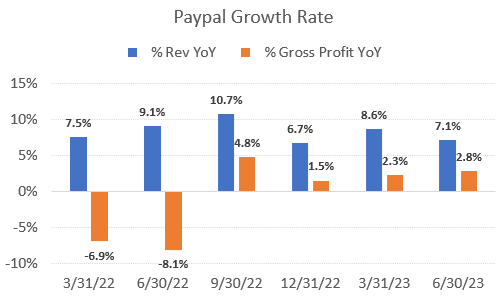

Whereas Paypal is growing revenues at high single digits, their gross profit growth rate has been hovering around 0%, indicating top line growth is coming from very low margin sources (i.e. Braintree).

Stratechery recently did a great interview with Lisa Ellis, who’s currently covering payments at MoffettNathanson, previously at Bernstein. She added some useful insights here on Paypal’s poor gross profit performance:

“And actually, if you back out the effective interest income, because they generate interest on the balances that people have stored in their wallets, which of course is getting a big boost because of higher interest rates. If you back out that effect, those gross profit dollars are actually down, and that’s what is causing the pressure on the stock because it feels to investors, this is empty calories and a race to zero.”

Other analysts note that the large legacy acquirers in the US are fighting back, the likes of Chase, Fiserv, FIS (WorldPay), and Global Payments. Taking a strategy akin to Paypal, they are pricing very competitive to gain business in payment processing, aiming to bundle in higher margin services where they can make a buck. Chase as an example can bundle in additional banking services.

Shift4 is another recognizable name in this space, but they are more focused on traditional merchant acquiring. Going through their recent wins, it’s practically all payment processing in the physical world, i.e. hotels, restaurants etc., although they also provide an online gateway for e-commerce. So they’ll be able to compete for a certain amount of business in the US with Adyen as well.

Let’s take a look at the startup scene for potential sources of new competition. Naturally Adyen-like copycats have emerged as well. Checkout.com is probably the largest of these with the company being valued at $11 billion last December. From their website: “Get the same payment gateway tech in all your markets. We help build your business, convert more sales and cut payment processing costs in over 150 countries. All of this by offering diverse payment methods, domestic processing and expert support from teams on the ground. With our modular technology you can seamlessly add the features you need, manage risk and fraud, and add new payment methods to support your growth in multiple new markets.”

Sounds familiar?

The company like Adyen boasts an impressive roster of clients, and according to the Financial Times they are also serving Netflix.

Nuvei is another one, how the company describes their capabilities on their website:

Nuvei is expected to generate $1.2 billion in revenues this year, although analysts are estimating a lower growth rate than Adyen’s in the coming years (high teens vs Adyen’s low twenties). They list the below names as clients:

Overall these are somewhat less impressive client names than Adyen, Checkout, or Braintree have — but clearly this is a company which will be able to compete for a certain amount of business and likely more so in the future.

Adyen’s biggest problem: clients are shifting volumes

What’s additionally troubling for Adyen is that enterprise customers already have a second payment processor built-in into their systems. So if one goes down, the codebase can call the other one to process transactions. Last week, Square took a timeout lasting almost 24 hours which is obviously a disaster for the small merchants running on their software. Business came to a standstill for a whole day. This is something a larger corporation will want to avoid at all costs. Some examples here: Shopify uses both Stripe and Adyen for payment processing, Booking.com is using Braintree and Adyen, Netflix is using both Adyen and Checkout, and Amazon is using Chase and Stripe.

What also seems to have happened during the first half of this year, is that enterprises have been shifting volumes away from Adyen towards other processors. This can be simply be programmed into the source code. For example, what you could do, is that you first call Braintree’s or Chase’s API to see if they can process the transaction. If it works, great, you’ve just made use of their lower take rates. If it doesn’t — let me try Adyen and their more advanced system and see if they can process it. A set-up like this could be fairly easily programmed, in fact, it would take a few lines of code.

Well, what has happened isn’t as extreme as the scenario outlined above, but something like this could happen resulting in a large volume drop for Adyen. Note also that customers usually want a fast payments acceptance process, especially for in-store transactions. So typically they will want to avoid having to use two processors in the same transaction. But reading analysts’ reports, they’re talking about a certain amount of volumes shifting to the second payments provider. For example, whereas before you might have sent them 20% of volumes, this shifted upwards during H1.

Adyen’s CEO at the Goldman conference gave some hints how a large customer like Ebay has been shifting some volumes away from them: “So of course, we've been working with Ebay now for the last five years or so. The idea was for them to take more control over the payments flow. I think they've done that quite successfully and we provide the technology for that. Of course, as you get to full capacity, you also decide what you do yourself and what you use your payments partner for. There are certain payment methods where you can take a choice of integrating directly or doing that through a payments partner, things like Amex or PayPal or a few of those types of examples. So that's the pace that they're in now.”

And on the H1 call, he touched upon how clients shifting volumes is something which is more easy in North-America: “If you look at online where we started the company, we see lower growth than what we hoped for. And the reason for that is that we have seen increasing competitive pressure in North America, and that's to my view related to a higher interest rate environment. More companies are looking at the bottom line, and that's an environment in which they try to see if cheaper alternatives work. It's the part of the business that's easiest to switch, US online. They give it a shot and they try to work with a lower cost provider. And it's something that we've seen also in the years behind us, but we also saw volumes coming back then. So it's not really new, but we've never seen it so concentrated as we do see it now.”

Lisa Ellis touching upon the volume shift as well: “You might have 80% (volumes) here, 20% there, or you might in the US even have three (providers). And you’re sort of turning, adjusting across those. So it can happen quickly, which is what Adyen has experienced, and it took them by surprise because it’s not like they lost the customer. It’s not like the customer renegotiated their contract. It wasn’t even necessarily visible to them until they started to see the impacts of it.”

The most lucid explanation came from Payal’s CEO: “We are going to drive hard on our PSP (payment service provider, i.e. Braintree) businesses. We are winning in the market. You can see it in the results of our competitors as well. And the way that it typically works is we grab like 20% of a very sophisticated merchant, the Ubers of the world, the Airbnbs, Spotifys, DoorDash, you name it. Most of the big ones are using us now. We come in, we grab about 20% as an alternative provider. And then what happened — and pricing is always competitive there — then vendors or merchant partners evaluate you on uptime. They evaluate you on auth rates and loss rates. And typically, what we find is we go in at 20%, our uptime is equal to or better than any of our competitors, and our auth rates and loss rates are better. We have more data, more information. We go from 20% to 40% to 60% to 80% to 90% of the traffic over anywhere from like 6 months to a year.”

Now obviously part of this is BS, Braintree won’t be able to beat Adyen on uptime, loss rates, or auth rates, but they are beating them on price. And hence the volume shift. The US, but I suspect also global e-commerce more in general, is clearly a highly competitive market, or in case of the latter is in the process of becoming one. Payments players are going after market share by downpricing. This is never a good situation for investors. How is Adyen responding to this?

At this moment the company isn’t looking to lower their prices to win business. They believe that the functionality of their platform will keep driving revenue growth for them, both with new clients onboarding as well as growing with the existing ones. Adyen’s CEO view is that due to their platform’s better authorization rates, the total cost of ownership for the client is lower. So the client pays a bit more on the take rate, but gets better authorization rates — which translates into higher revenues — and better functionality in return (e.g. fraud detection). He also explained that the company is working on reducing interchange fees for their clients — i.e. the fees collected by Visa and Mastercard which range from 1.5% to 2% in the US — although no details were provided here how they would manage this. The company is holding a capital markets day in November so they’ll probably outline how this might work then.

Adyen’s H1 report provides some examples of how they are investing to differentiate their platform: “Powered by machine learning, we launched two products that turn complexity into conversion and realize iterative revenue uplift. The first, Data-Only, taps into Adyen’s global insights to improve authorization rates even in regions where strict authentication regulations are not in place. When a transaction is executed in the United States or Brazil, for example, Adyen voluntarily shares relevant authentication data with schemes for more informed authorization decisions. Alongside our Data-Only product, we launched Trusted Beneficiaries, through which shoppers in the checkout stage can add a business to their list of trusted companies. After designating a business as such, shoppers will not need to be re-authenticated when purchasing from them in the future. This again brings added convenience to the consumer and increased conversion to our customers. Together, our Data-Only and Trusted Beneficiaries authentication capabilities help businesses broaden their decision-making resources, increase conversion, and reduce fraud.”

So obviously these are nice features, but replicable by competition. All you need is some coding and data science talent. I give credit though to Adyen that it is a company focused on innovation while the business is printing healthy margins and profits, unlike a lot of other tech companies.

Another problem however is that Adyen’s founder and CEO had to take a medical leave, after which the CFO was promoted to co-CEO. Resulting in the COO deciding to leave. So there has been quite some change in the top management, but the November capital markets day could also address this.

Also Paypal’s CEO is leaving but perhaps there could be an opportunity here for Adyen. We don’t know what the new CEO’s view on strategy will be, so there is the potential that Braintree’s competitive stance might change. Although I wouldn’t bet on it given the share losses they’re suffering in their core Paypal business. Paypal’s new CEO is coming over from Intuit, where he seems to have built up a good track record.

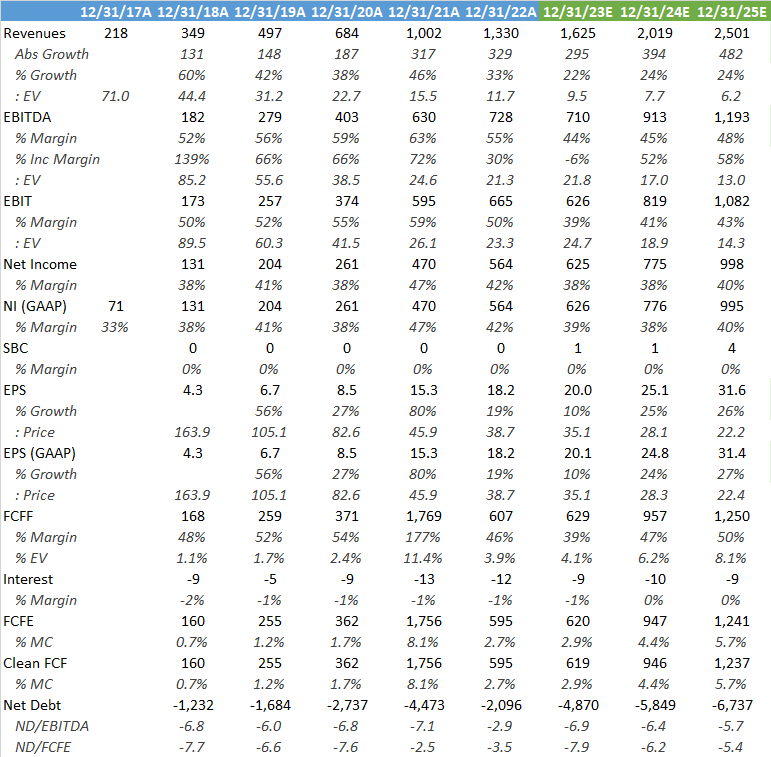

Financials - share price of EUR 703, ticker ADYEN on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange

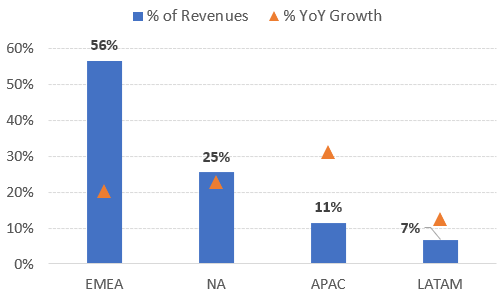

In H1, 56% of revenues for Adyen came from EMEA, 25% from North America and 11% from APAC. The latter is the highest growth region but also Europe and North America are still growing at rates of 20%.

Adyen aims to grow revenues at a CAGR of 25 to 30% in the coming years, while guiding for EBITDA margins to move up to 65% over the long run. If they can make these targets, obviously the shares will work very well.

The sell side’s estimates for the company are shown below. If I put 2025 EPS on 25x, I get to a 13% IRR assuming that the attractive FCFs they are generating can be returned to shareholders as well, given that the company is sitting on a load of cash already. They did mention that they will maintain large cash balances going forward to preserve their high credit rating. However, given the competitive environment, these estimates could easily turn out to be overly rosy.

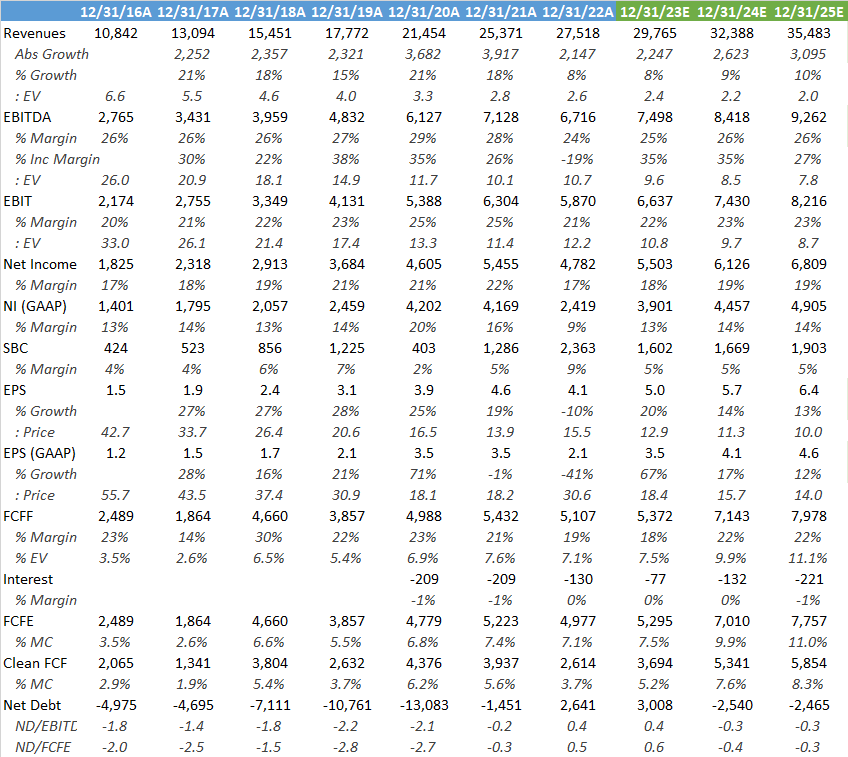

The same table for Paypal below — top line growth has fallen now to single digits in combination with falling margins. Taking into account the SBC, the clean FCF yield was 3.7% in 2022, with an expected GAAP PE of 18x for this year. In my opinion, this looks expensive for a business dealing with substantial pressures. Its core payment button is commoditizing and the company is likely to continue to suffer from further market share losses here. As this is the bread-and-butter profits generator of the company (around 50% of gross profits), there is a clear risk that profits will head south in this area. And as Braintree is heavily discounting on price, profit contributions from this area will be too limited to offset this (Credit Suisse estimates Braintree to contribute 5 to 10% of gross profits).

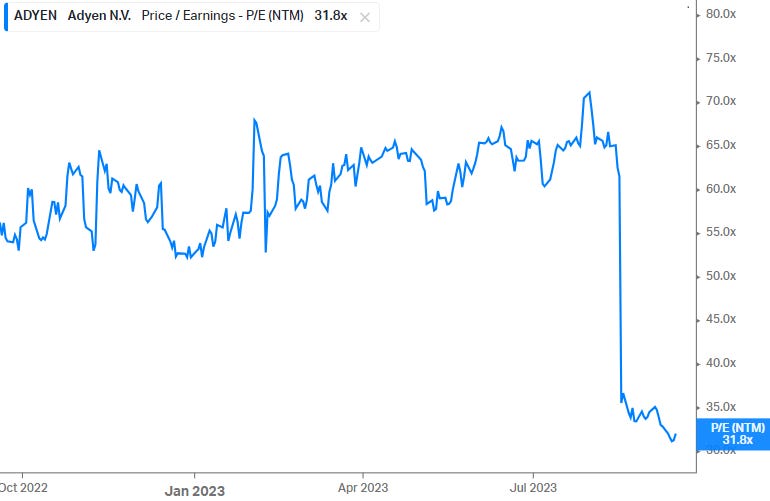

Adyen’s next-twelve-month’s multiple has fallen from 65x to 30x EPS after the recent results. However, given the pressures the company is dealing with, I would rate the risk-reward as fairly balanced at this stage and I wouldn’t say the shares are cheap.

On the positive, the company is still growing their top line faster than the e-commerce market, and although margins have been falling, the company is still expected to grow EPS at a 10% rate this year. Which should be a peak year in terms of headcount investments. Obviously there is substantial potential for further growth, but on the flipside the competitive environment has clearly increased and it seems likely that this will only continue. Not only from Braintree but also with new competitors emerging, such as Stripe moving upmarket, and Checkout and Nuvei becoming more competitive.

A lot of comparisons are being made that Paypal is like Meta at the end of 2022. Meta was completely different — it’s basically a sound business where Zuck had simply decided to start burning his free cash flow like a madman. As soon as he announced Meta will start allocating cash with sense, credit to Brad Gerstner here who wrote an excellent shareholder letter, EPS projections took off and the stock rallied. Paypal is completely different with the company struggling from competition.

If you enjoy research like this, hit the like button and subscribe. Also, please share a link to this post on social media or with colleagues with a positive comment, it will help the publication to grow.

I’m also regularly discussing tech and investments on my Twitter.

Disclaimer - This article is not a recommendation to buy or sell the mentioned securities, it is purely for informational purposes. While I’ve aimed to use accurate and reliable information in writing this, it cannot be guaranteed that all information used is of this nature. The views expressed in this article may change over time without giving notice. The future performance of the mentioned securities remains uncertain, with both upside as well as downside scenarios possible. Before investing, I recommend speaking to a financial advisor who can take into account your personal risk profile.

Appreciate your write-up and find it hard to argue against - the payments space is highly competitive and as Ms. Ellis highlighted, essentially a race to zero (particularly in the US).

One area I would caution you on is that everyone seems to not understand the nature of Adyen's business, at least when it comes to the cash flow statement. FCF is perpetually overstated because people seem to believe receivables from/payables to merchants are legitimate cash flow, but they're more like very short-term float. Sure, you can rake some interest income off of it, but you can't use that money to invest in the business (at least not if you're an upstanding company).

As such, I get Adyen's 2022 FCF to be closer to EUR 450m, down a bit from 2021. Even if you were to take the sell-side models at face value, I found it interesting that you believe Adyen on a 2.7% FCF yield is a safer bet than PYPL on a 3%+ FCF yield citing a highly competitive industry as if they aren't each facing similar challenges.

I agree PYPL's checkout button is losing share to the likes of Apple (though the new/upcoming ability to pay with your PYPL account within Apple Pay may mitigate this to some extent), but as pointed out by others, Adyen doesn't even have this melting ice cube to subsidize the business.

Life won't get easier for anyone in this space and it could be argued the player with ~$2.5bn in legitimate FCF has a stronger beachhead than the one with <$500m.

with respect to this comment:

"I agree PYPL's checkout button is losing share to the likes of Apple (though the new/upcoming ability to pay with your PYPL account within Apple Pay may mitigate this to some extent), but as pointed out by others, Adyen doesn't even have this melting ice cube to subsidize the business."

as far as i know, there is no intention on apple's end to integrate paypal/venmo into the apple wallet. this, if true, would be very big news for paypal and help stop the bleed on the branded side of things, but as far as i know its not in the works. if you have proof otherwise i'd be interested!